I went to Young Involved Philadelphia’s City Council Candidate Convention last night. As I talked directly with many of the candidates, there was a common refrain among many of them: “The city needs to rebuild its tax base by bringing more jobs back into the city.” (The policy conclusions each candidates drew from that premise varied, of course.) And that’s true! But I think it focuses attention and energy in the wrong place, in part because I think that accomplishing that task as a first-order goal is hard, while the task “rebuild the city’s tax base by attracting new residents” is much easier, in part because it’s building on an already existing, successful, trend.

The issue is that our extensively decentralized job market isn’t going anywhere in the short term, but that alone doesn’t actually draw people to live in the suburbs. We live in an economy that is very, very short on job security, or any other form of loyalty between an employer and and employee. This cultural shift seems like it’s permanent, and it’s arguably a good thing for an economy trying to create wealth. A generation ago, a family might base a decision on where to live on minimizing commute time to the one or two specific jobs they already had. Today, they must base their decision on minimizing commute time to the entire set of possible jobs throughout the region. Even if most of those jobs are out in the suburbs, that pressure is going to bring a lot of educated, skilled workers into Greater Center City, and neighborhoods with fast and frequent transit access to Center City. Center City’s importance is not only as a job center in its own right, but as a transportation hub with direct connections throughout the region.

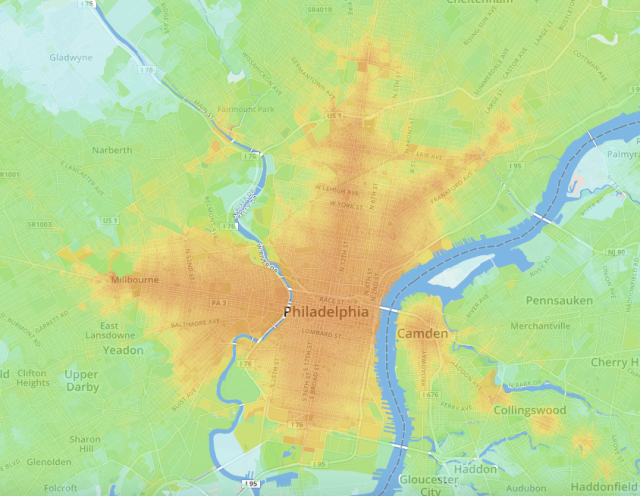

If you’d like a visual representation of what places this kind of job-access pressure is going to bring new residents to, look no further than this map produced by the University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory. (The project landing page, with links to their full 2014 report, methodology, and maps for other cities, is here.) Maps like this one, which measure the absolute number of jobs accessible by transit and walking in 30 minutes, can help policymakers understand where residential development pressure is likely to spread to, and which neighborhoods are likely to remain affordable indefinitely. It can also help transportation planners understand which areas are being poorly served by the existing transit network. That can boost the priority given to projects like City Branch BRT, which will give better, faster access to underserved Strawberry Mansion; or to projects that connect peripheral job centers to the regional network, like BSL-Navy Yard or NHSL-King of Prussia; or to initiatives that boost frequencies on Regional Rail lines and reduce waiting times for neighborhoods like Germantown and Manayunk, like the city did during the PSIC era in the 1960s and 1970s.

Bringing residents back is obviously not a panacea for what ails the City of Philadelphia, but it’s a good, necessary start. (Fixing the schools so that people don’t have to flee to the suburbs when their kids turn 5 is an obvious next step.) But in addition to directly restoring the income and property tax bases of the city, more new residents will bring new jobs with them as a trailing indicator. As I said, I don’t think the peripheral job centers are going anywhere anytime soon, but people generally eat, shop, and use services in the places that they live. Residents are customers for city-based businesses, old and new.

Not only will a continuation of the residential renaissance create new retail-level businesses and jobs, but there’s another, slightly more cynical mechanism that will cause jobs to follow people into the city: our old friends, the 1%ers. As Chester County native and proto-urbanist William H. Whyte (The Organization Man) noted in his 1989 book City, when corporate headquarters fled New York City to southwestern Connecticut in the mid-20th Century, there was no evidence to support the popular claim that businesses were fleeing onerous taxes in New York to lower taxes in Connecticut. Even then, taxes in Connecticut were substantially similar to those in the City. But there was a very strong relationship between the locations of the new suburban headquarters and where the CEOs of the companies lived; the average distance was eight miles. The development of ultra-high-end housing (like the $17.6M penthouse that was the subject of false rumors involving Jay-Z and Beyoncé) in the Center City core might look a bit unseemly at times, but if those apartments get bought up by C-suite executives, we can expect more corporate office towers (and their associated jobs) to follow them into our most accessible location. Maybe that process might involve a bit of promotion for our insanely competitive private schools, while we’re still working on the public ones. It’s not an equitable solution in the short term, but the potential upside in the medium term is awfully hard to argue with.

All this matters because many of our longstanding civic problems, like funding our public schools, counteracting the effects of poverty and income inequality, reducing violent crime, improving our public transportation system, and even picking up trash and litter from the streets, are primarily issues of funding. We simply can’t afford to do the basic tasks of city government with our current tax base in the long term. We can keep trying to paper over the difference with state and federal aid, but that’s not a good strategy in the long term. Making Philadelphia an attractive place to live makes all these problems tractable. Attempting to lock out newcomers, which is as likely to displace longtime residents as it is to actually dissuade New Philadelphians, will keep real solutions out of reach, for all time.

FYI, the 3rd paragraph is missing its end.

Thank you, fixed.

> Even if most of those jobs are out in the suburbs, that pressure is going to bring a lot of educated, skilled workers into Greater Center City, and neighborhoods with fast and frequent transit access to Center City

This strikes me as really a really important point, and heavily geography dependent. In Seattle you pretty much have to choose between reasonable commute to city jobs and reasonable commute to suburban jobs, because transport over Lake Washington is so constrained (busses help some, but there are last mile problems unless your job is in a narrow corridor). Plus west of Seattle is water, so it’s not the geographic center of jobs even if it has the densest concentration.